After much fanfare the FCA’s new Consumer Duty is now in force from today.

While consumers may not notice an immediate difference, the regulator is hoping the Duty brings about significant changes in the way the industry interacts with customers.

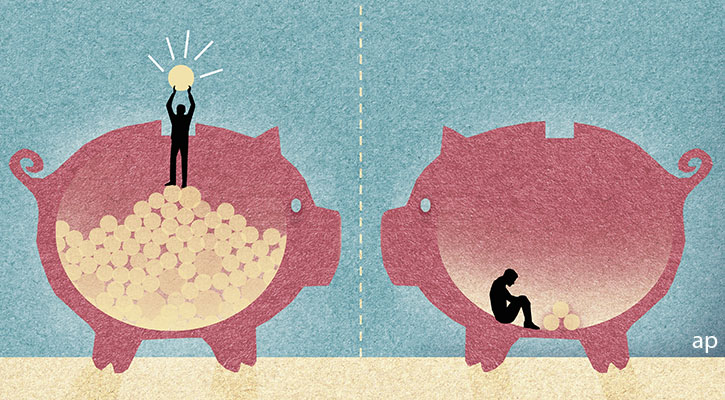

In essence, the Consumer Duty is designed to raise standards, improve service levels and value for money. Connected to these aims are an attempt to reduce scams and to help vulnerable people access products at affordable prices. Read more below.

What Are the Main Changes?

In the regulator’s words, financial companies will be expected to: provide helpful and responsive customer service; equip their customers to make good decisions through communication people can understand; and provide products and services that meet consumers’ needs and work as expected.

They will also have to explain and justify their pricing decision, answering questions like: does this product offer fair value and why?

What Does the Regulator Say?

The FCA describes the Consumer Duty as helping consumers at every stage of the "journey" – from initial contact to closing an account because you’ve found a better deal or are unhappy with the way you’ve been treated.

"People should know what they are paying and know what they are getting for what they pay," says Nisha Arora, director of cross-cutting policy and strategy at the FCA.

The FCA is putting a premium on improving the way firms communicate with customers and making it easier for them to complain and switch.

"It's really important consumers still shop around for the best deals, but firms need to give them the right information so they can make those decisions," Arora says.

"What we want (firms) to do is make it as easy to switch, complain, move product or service, as it was to come in, and not have to go through all those hoops and hurdles to make things happen."

What Does the Industry Need to Do?

Avording "harm" and achieving good "outcomes" are key phrases.

James Jones-Tinsley, financial planner and Sipp technical specialist at Barnett Waddingham says "the overriding mantra of the Duty is for providers and advisers to both challenge and avoid foreseeable harm to customers, and in doing so, achieve good outcomes for their customers".

A lot of work has been going behind the scenes at financial firms in terms of training and getting up to speed with the new rules, with the FCA prompting companies way ahead of today’s changeover.

The FCA says most firms are ready, but others are not, despite having a few years to get up to scratch – after all the expanded Consumer Duty proposals were laid out in 2021.

What’s the Background?

Since the financial crisis of 2008-2009, banks in particular have been trying to rebuild trust with customers. To use the corporate language, this process remains a "journey" rather than a destination.

Just in time for the launch of the Consumer Duty, the FCA’s Financial Lives Survey from 2022, released last week, revealed how much work needs to be done.

A key finding was just 41% of those surveyed in May 2022 had confidence in UK financial services and 36% thought most financial firms were honest and transparent in the way they treat customers.

One potentially encouraging discovery, at least for the banks, was that they rate higher in terms of trust than pension funds, financial advisers and fund firms. This could be a reflection of higher approval ratings for "disruptive" fintech banks that have no branches and whose accounts can be opened and managed via an app.

Banks can never feel complacent about their standing in British society, as NatWest can attest to after a damaging month.

The Farage saga may seem remote to most people, but it has highlighted a key principle over access to banking services. The media may be confusing the "debanked" – millionaires who lose access to prestige services – with the "unbanked", who are locked out of the financial system due to poverty, homelessness, or other afflictions.

But the principle is an important one; if you don't have a bank account, you're effectively shut out from the modern world.

High street banks have also been criticised for not passing on rate increases to savers. At the same time, they're the ones putting up mortgage rates to levels unthinkable a year ago.

It may be harder to generalise about the allegations against Crispin Odey – and the financial fallout – but the best that could be said is that the episode is not a great advert for founder asset management firms. Or how non-financial conduct is not adequately caught in the current regulatory net; UK editor Ollie Smith looks at this tension at the heart of the system in detail.

The Consumer Duty will also never rid the UK of rogue advisers, bad fund managers, scams, poor value products or dismal customer service; like all dynamic systems it’s never going to be 100% free of dissatisfactory "outcomes" for consumers. But the reasoning behind it is that by labelling the new rules as "duty", the worst-performing or "must improve" firms will have to raise their game – or face censure from the FCA.

What About the FCA’s Role?

In a perfect world, a powerful and faultless regulator would hand down new edicts to companies that promise to do better. But the Consumer Duty has arrived at a crucial time for the FCA as it fights to maintain its reputation after a number of scandals.

According to last week’s survey results, two‑thirds (65%) of adults were aware of the FCA. But of those who were aware, just over a quarter (27%) had high levels of trust in the FCA to protect their best interests as consumers.

Even the government appears to be less supportive of the regulator’s aims at this point; City minister Andrew Griffith, whose profile has been raised by intervention in the Coutts/Farage episode, is apparently sceptical of the Consumer Duty because it increases the regulatory burden on firms.

This clash of cultures between the regulator and a government keen to loosen regulation is unlikely to be resolved. Crypto provides a key example: the government can see the benefits of bringing the industry under its purview, but the FCA is being put in an uncomfortable position because it’s spent the last few years warning consumers to avoid it.

If you’re a Treasury official, you may think the FCA has too much power, and that the vast regulatory infrastructure built up since the financial crash of 2008 is now in the way of reviving the City and improving the listings environment.

Jeremy Hunt talks frequently about deregulation as a way of unlocking growth. But consumers may see this completely differently, and ask why, if there are so many rules surrounding financial services, does my experience with financial services still fall short?

If it can indeed assist, that is not a question the Duty will be able to answer quickly.