Professor William Sharpe won the 1990 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for developing the capital asset pricing model, which, among other things, asserted that a stock's expected return depended upon only a single factor: its "beta".

The Greek name aside, the statistic is straightforward. Beta measures how a stock's price tends to change, based on the market's overall performance. By convention, the market beta is set at 1.0. Thus, stocks with betas of 1.20 will typically move 20% further than the averages, while those with betas of 0.70 will shift 30% less.

How Does Beta Work?

Sharpe's insight was that, because investors can diversify to protect against other equity-related risks (such as the possibility that specific companies or industries will founder) what matters for determining a portfolio's expected return is its aggregate beta – the asset-weighted average of its equity holdings. Per Sharpe's analysis, beta cannot foretell how the overall market will fare, but it can suggest the level of a portfolio's returns, assuming a given stock market result.

To be sure, beta cannot specify every company's outcome. It describes the conduct of large numbers, not single situations. Thus, when Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A) and Enron each faced a losing stock market in 2001, while possessing similar betas, Warren Buffett's firm managed a small profit while the latter lost 97%. In addition, betas cannot be determined in advance. They can be estimated from stocks' historic returns but not definitively known before the fact.

All fine. Nobody expects beta to predict either individual stocks or portfolio performances over short periods. Sharpe's hypothesis addresses general long-term actions. To cite one example, it implies that, if the stock market were to increase over several decades, growth stocks should outgain value stocks, because, on average, they typically have higher betas.

Beta's Real-World Results

Therein lies the problem for Sharpe's model.

When the professor first floated his concept in 1964, nobody could refute it. The capital asset pricing model was based on theory, not observation. In those days, finance professors were few and high-powered computers rare. The research had not been done to assess whether, in fact, beta had explained equity returns.

By the time Sharpe received his Nobel Memorial Prize, that task had been completed – and its findings were devastating. Concluded future Nobel laureate Eugene Fama, who (along with Kenneth French) refuted Sharpe’s thesis: "Beta as the sole variable in explaining returns on stocks is dead".

The wording was kind. Not only had the authors discovered no link between beta and stock performances, but they had also shown value stocks had walloped growth stocks. Less risk, more return!

The Beta Field Test

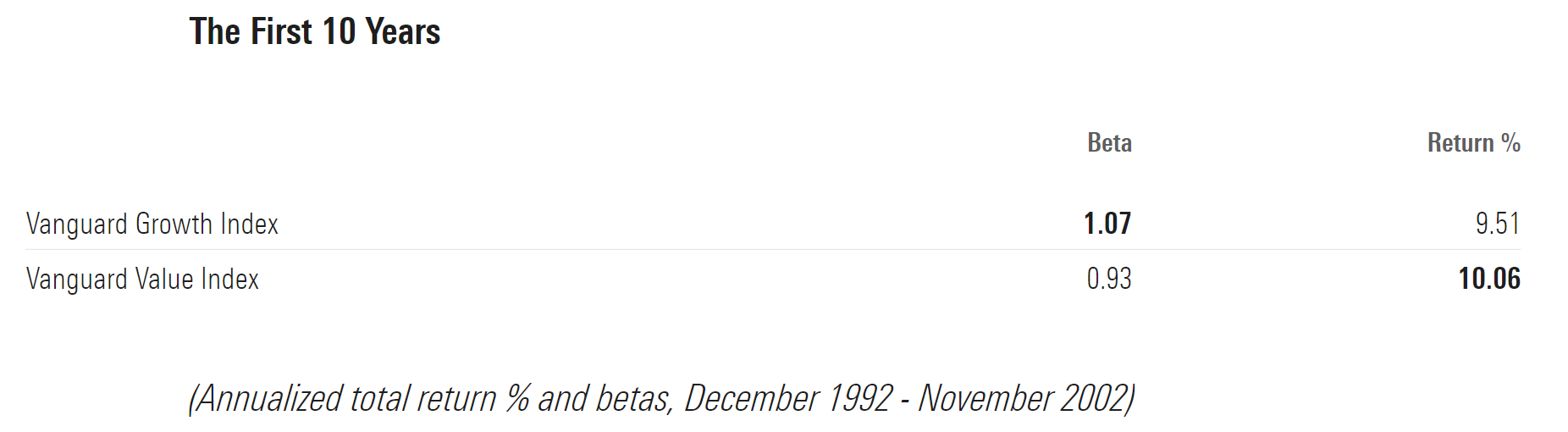

In November 1992, Vanguard launched two style-index funds, which divided the S&P 500 into opposing segments: Vanguard Growth Index (VIGRX) and Vanguard Value Index (VIVAX). For the first time, albeit indirectly (as these investments were not officially built to deliver high and low betas, but they did so in practice), observers could readily test whether beta operated as advertised.

For the first decade during those funds' existence, it did not. As expected, Vanguard Growth Index's beta was well above that of Vanguard Value Index. Its returns were closer to the mark, but they nevertheless trailed through a mostly rising market, which (again) was not how beta was supposed to work.

After that result, academic opinion was almost entirely united. Another 10 years of value-stock success confirmed the researchers' initial suspicions. Whether value stocks won because investors were irrationally wary of them, as behavioural economists argued, or because they carried meaningful risks the beta measure overlooked, the reality had been ascertained. Beta was well and truly dead.

Except that it wasn't.

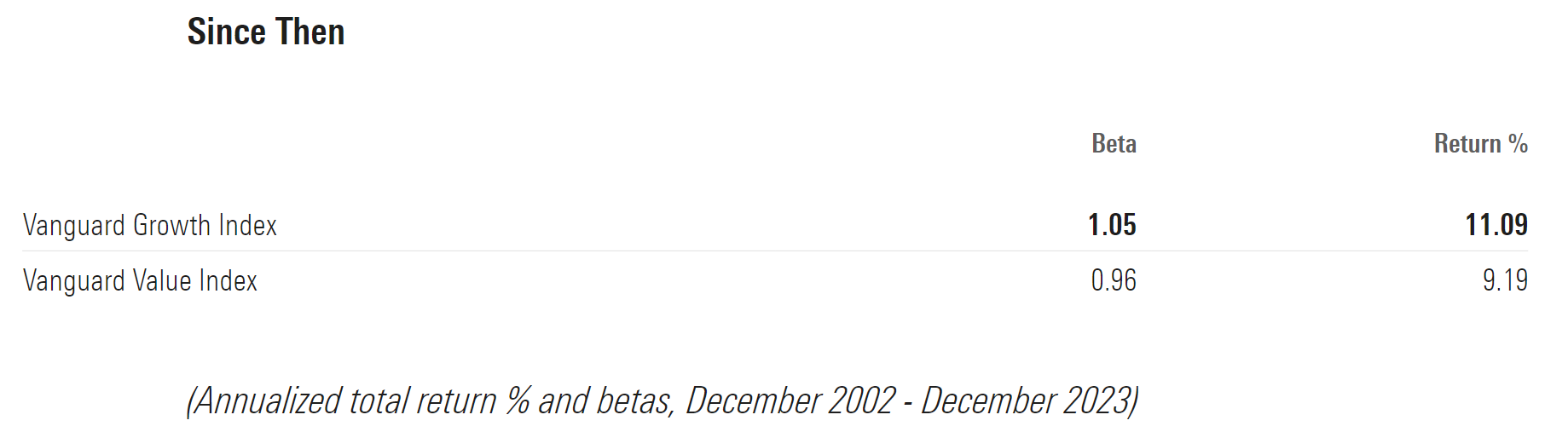

Since Vanguard's style-index funds celebrated their 10th birthday, the pattern has neatly been reversed. Not each funds' beta. Over the next 21 years, they remained almost unchanged. Once again, Vanguard Growth Index’s beta surpassed that of Vanguard Value Index, although the gap did narrow slightly. But the relative returns flipped, with Vanguard Growth Index outgaining its sibling by almost 2 percentage points per year.

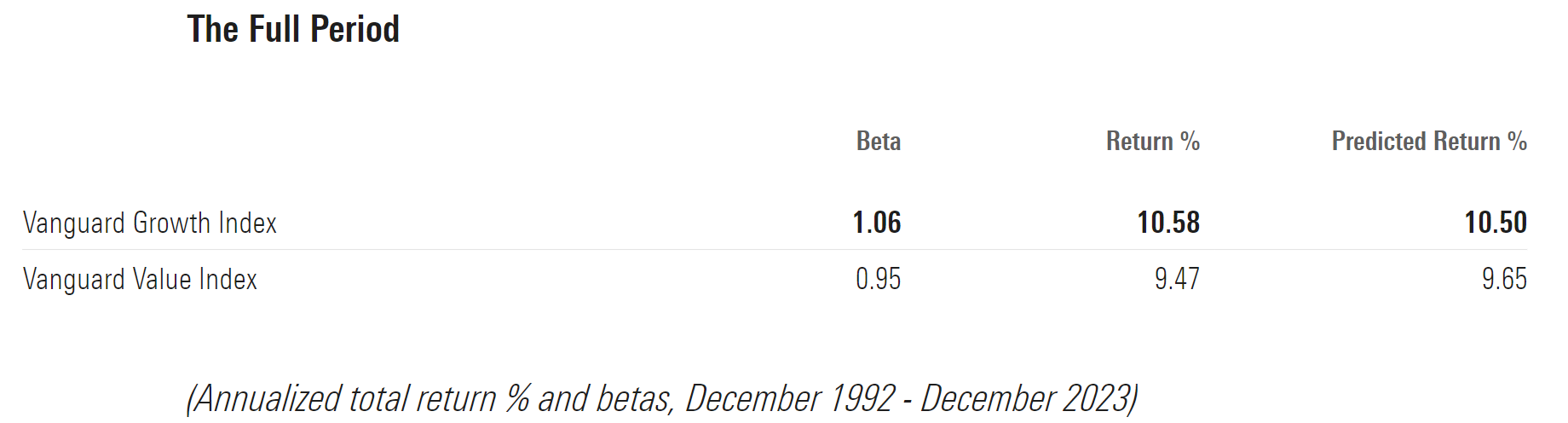

Assessing the post-1992 record in this fashion, by splitting the results into a 10-year period and then a 21-year stretch, is of course an arbitrary decision. I did so to demonstrate how thoroughly beta had been discredited by the early 2000s, when its predictive power appeared non-existent. A fairer approach to the data is to avoid such tricks by presenting the 31-year record in its entirety.

The table below does that, along with showing the predicted return for each fund per Sharpe's formulation (which requires in addition to the stock market’s results the rate of risk-free return, which averaged 2.31% over the period).

Final Thoughts

Few investment theories have truly been validated. It's clear that, for developed nations with healthy economies, stocks will almost always outgain bonds over time. (That statement may not necessarily hold for emerging countries, a topic that I will address in a separate article.)

No special insight is required for that observation. In June 2003, a 30-year Treasury bond paid an annual $48.10 (£37.91) for each $1,000 par value. It still does today. Meanwhile, one share of Microsoft (MSFT) stock in June 2003 earned the right to $1.37 of the company's operating cash flow. The current amount is $11.79. True, Microsoft has been unusually successful, but the principle remains. In aggregate, companies grow their businesses rapidly enough to reward their shareholders.

After that, though, investment theory is just that – a theory. The hypothesis may eventually be ratified, but it also could be incorrect. Or, more likely, it contains some truth but not enough to serve as a meaningful predictor. That precept is worth considering the next time a fund marketer presents an investment strategy that has been "proved" by academics.

John Rekenthaler is vice president for research at Morningstar