In September, the first group of British 18-year-olds received the proceeds of a gift given them by the government when they were born.

That gift was £250 (or £500 for children of disadvantaged families) in the form of a Child Trust Fund, introduced on September 1, 2002. Those children turning seven before August 1, 2010 also received a top-up. In 2011, the entire scheme was replaced by the Junior Isa, but by then some 6.1 million newborns had already received a CTF voucher.

New research from my US colleagues demonstrates how the core of the CTF was a good idea, but in hindsight perhaps an opportunity missed. Implemented differently, the positive concept could have had a more far-reaching impact for both individuals and society. The research explores an idea called “baby bonds,” originally proposed by two academics: Darrick Hamilton and William Darity.

As with the CTF, the government would contribute to savings accounts for children under 18, with the contributions determined by family income or wealth. To work in the UK, however, there are some key differences with the US proposals:

1. Contributions would be regular, rather than one-time, thus building a more meaningful pot

While the government contribution to CTFs was small, parents were able to supplement the investment in the tax-free scheme on an ongoing basis. And when the CTF scheme was stopped, the pot could be transferred into a Junior Isa, where the yearly contribution limits have more than doubled to £9,000 today. But although the scheme and the government contribution was provided to all children, it was principally of benefit to those families with a degree of financial market knowledge and available funds to invest. Indeed, over 1.7 million children’s accounts were opened by the government on behalf of those whose parents never actioned their voucher

2. More constraints on where contributions should be invested

CTF vouchers could be put in one of three places: stakeholder accounts, where annual fees were capped at 1.5%; cash deposit savings accounts; and investment fund accounts. Fortunately, the default account type was the stakeholder, meaning that most were invested in stock markets rather than in cash. However, we generally prefer fee pressure to come from market competition than regulator imposition. That’s because it’s very easy for a maximum to become a de facto minimum charge in practice, so unless the maximum is set at the lower end of typical market rates, investors can lose out. This is what happened with some CTF stakeholder products invested in index tracking funds, which had an annual charge of 1.5% when similar funds could be bought for less than 0.5% in other accounts.

3. When recipients turn 18, their use of the proceeds would be more targeted

CTF beneficiaries are free to do as they wish with the money when they turn 18. In the US, the options would be limited to using the accumulated savings to pay for expenses such as college, purchasing a house, or other “wealth building” activities that are not fully specified. This approach correlates more with the newer UK Lifetime Isas, where young people can save or invest in a tax-free account and have it supplemented by an annual 25% government bonus, with the proviso that the funds are used to either fund a first property purchase or retirement.

Our US research specifically examined whether a baby-bond program could address the racial wealth gap, which events of this year have thrust back into the broader consciousness. According to the Survey of Consumer Finances, white families had more than seven times the wealth of the average black family in 2019. Furthermore, that ratio has not moved meaningfully in decades. Income gaps between races in America are also high – white families had a median income of more than $70,000 compared with a touch over $41,000 for black families – but not nearly high enough to fully explain the wealth gap.

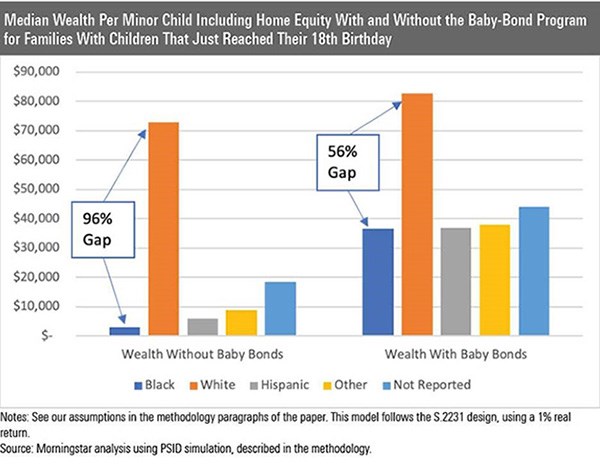

The answer to whether baby bonds could help close the wealth gap, then, is a resounding yes.

The chart below shows the difference in the racial wealth gap before and after we simulated the effect of introducing baby bonds. Baby bonds could cut the racial wealth gap in half in terms of resources available per child at age 18.

To be clear, the limitations of the UK CTF are not all addressed by the US proposals, and conversely, CTFs had some features that have not yet been addressed in the US.

CTFs, for example, had the advantage that they could be invested in savings, fixed income or equity securities, while the baby bond proposals would see investments in treasuries, giving more predictability and security of returns at the cost of potential higher growth. CTFs can also be rolled over into other tax-advantaged accounts, so that recipients can choose to continue growing their accumulated savings free of tax.

While the perfect solution may not yet exist, policymakers need to explore ways to ensure that 18-year-olds get good advice for making such investments. That is as true in the US as in the UK.

For more information on baby bonds, download the full report.